When drafting an appeal brief for ex parte appeals at the USPTO, one of the primary guidelines the USPTO emphasizes is to present only the strongest arguments. See the link (here), where the Office presents their top practice tips. Three of these deal with this issue (reproduced below):

-

Present only the strongest arguments.

-

Do not dilute strong arguments by including weaker arguments or arguments that have no bearing on the issues in the case.

-

Give careful thought to which claims you choose to argue separately so that weaker arguments do not dilute stronger arguments.

This advice aims to help applicants focus on the most compelling points, potentially increasing the likelihood of a favorable outcome. However, the rules governing ex parte briefs at the USPTO do not impose a page limit. This lack of restriction introduces a strategic challenge: while conciseness is valued, the unpredictability of the panel’s reception to various arguments means that excluding certain arguments could jeopardize the appeal.

Given the situation, patent attorneys often face the dilemma of balancing thoroughness with clarity (and cost to the client). Although the USPTO recommends focusing on the strongest arguments, the possibility that any argument could sway the panel suggests that, for at least some cases, presenting a broader range of arguments might be prudent. This is especially critical considering that any argument not raised in the initial appeal brief is deemed waived in future proceedings. Consequently, omitting an argument that might later be considered significant could severely undermine the case.

In a recent appeal before the PTAB (Appeal 2023-000836, Application 16/299,561), Bissell faced this issue head-on. The invention relates to an air purifier mounted in furniture. Claim 22 on appeal is reproduced below.

22. A room air purifier, comprising:

a body at least partially defining an interior chamber and an opening to the interior chamber, the body having a top, a bottom, and a plurality of sides, wherein at least one of the plurality of sides includes the opening;

a panel configured to removably mount to the at least one of the plurality of sides and cover the opening to the interior chamber;

a purification mechanism in the interior chamber including at least one filter and at least one blower, wherein the purification mechanism is configured to generate an inflow through the panel and an outflow to an exterior of the body through at least a portion of the top of the body;

a base mounted to the body;

a set of legs coupled to the base; and

a nonwoven fabric portion covering at least part of the body.

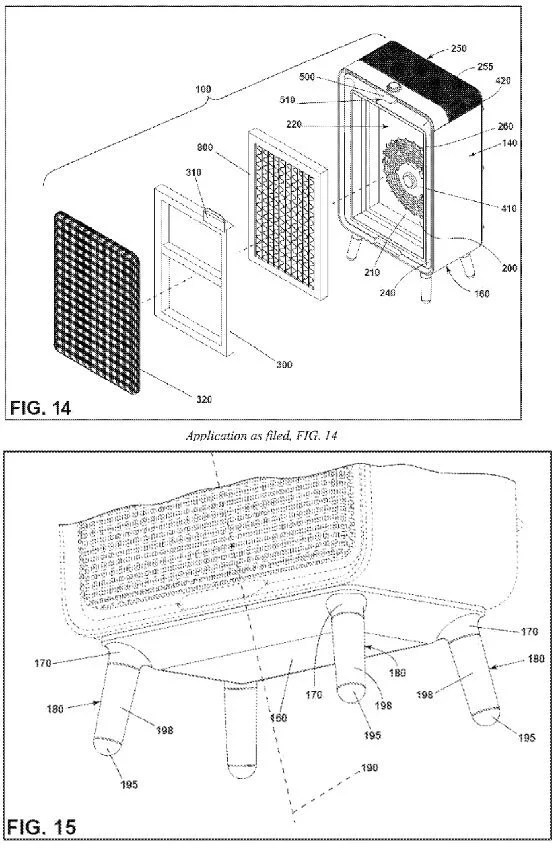

Figs. 14 and 15 below illustrate an example detailed embodiment of claim 22. One issue in the appeal related to the base mounted to the body (elements 160, 140, respectively).

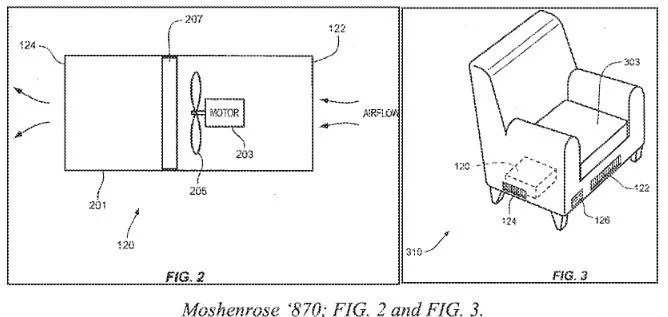

The examiner relied on prior art showing a chair, alleging that the figures (reproduced below) show a chair 310 having body and a base mounted to the body, with legs coupled to the base. As can be seen from Fig. 3 below, the legs are mounted to a singular chair body.

The appeal brief presented six separate attacks on the obviousness rejection of claim 22 (a-f). The Board ignored the first five arguments, which included issues such as non-analogous art, altering the principle of operation, no reason to make the combination, hindsight bias, etc. However, argument (f) alleged that even if combined, certain features were missing. Argument (f) essentially came down to a claim interpretation issue.

Specifically, Bissell’s argument (f) asserted that the term “base” required a separate structure from the body and could not be satisfied by, for example, merely the bottom surface of the chair.

While there may be PTAB panels that would side with the examiner on this issue (which perhaps influenced the number six position of this argument in the brief), the panel here agreed with the applicant. From the opinion (citations omitted):

Claim 22 recites that the claimed room air purifier includes a body having a top, a bottom, and a plurality of sides, a base mounted to the body, and a set of legs coupled to the base. The plain language of claim 22 requires the body and the base to be two distinct elements of the room air purifier. The claim recitation of a base “mounted to the body” is consistent with the foregoing interpretation. This interpretation of the plain language of claim 22 is consistent with the disclosures of the Appellant’s application. … As discussed above, the Examiner finds that Moshenrose’s chair 310 corresponds to a room air purifier. It is not entirely clear on the record before us which component or portion of chair 310 the Examiner relies on as corresponding to a body as recited in claim 22. Regardless, however, the Examiner does not identify a first element of chair 310 that corresponds to a body, and a second, separate and distinct element of chair 310 that corresponds to a base mounted to the body, as required by claim 22. In particular, the Examiner does not identify two distinct and separate elements of Moshenrose’s chair 310 that correspond to (1) a body having a top, a bottom, and a plurality of sides, and (2) a base mounted to the body, where a set of legs is coupled to the base. The Examiner, therefore, does not provide a sufficient factual basis to establish that Moshenrose discloses or would have suggested a room air purifier including a body having a top, a bottom, and a plurality of sides, a base mounted to the body, and a set of legs coupled to the base, as required by claim 22.

While all the applicant’s arguments may have been strong, it can be hard to predict which one might carry the day. For sure there are statistics that point to the difficulty of non-analogous art, or the higher success of arguing missing elements, but at the end of the day the facts of each case tend determine the outcome.

Therefore, one might consider a comprehensive approach that includes both the strongest and supplementary arguments for ex parte appeal briefs at the USPTO. This strategy ensures that all potential avenues for success are explored and preserved for future consideration. While this might result in a longer, more detailed brief, it provides a safety net against the unpredictable nature of the appeal process. Experienced attorneys can employ various techniques to manage this expanded content effectively, such as clear headings, subheadings, and concise summaries, ensuring that the brief remains organized and readable despite its length. While the USPTO’s top tips of presenting only the strongest arguments serves as a useful guideline, the nuances of ex parte appeals necessitate a more nuanced approach.

Leave a comment