Rejections by patent examiners at the USPTO should be based on evidence. Of course, it is hard to find a clear statement requiring this in the MPEP. There certainly are specific areas where the MPEP references the requirement for evidentiary support of rejections, such as MPEP 2144, 2112, 2141, and so on. The “should” terminology is set forth is MPEP 706, but more in the opposite context of when to reject:

The standard to be applied in all cases is the ‘preponderance of the evidence’ test. In other words, an examiner should reject a claim if, in view of the prior art and evidence of record, it is more likely than not that the claim is unpatentable.

However, one place where the PTAB looks hard at the evidence is where it is possible for the applicant to show that the Examiner’s rejection is based on speculation. Once the applicant can establish speculation, it is then generally an uphill battle for examiners (assuming they even try).

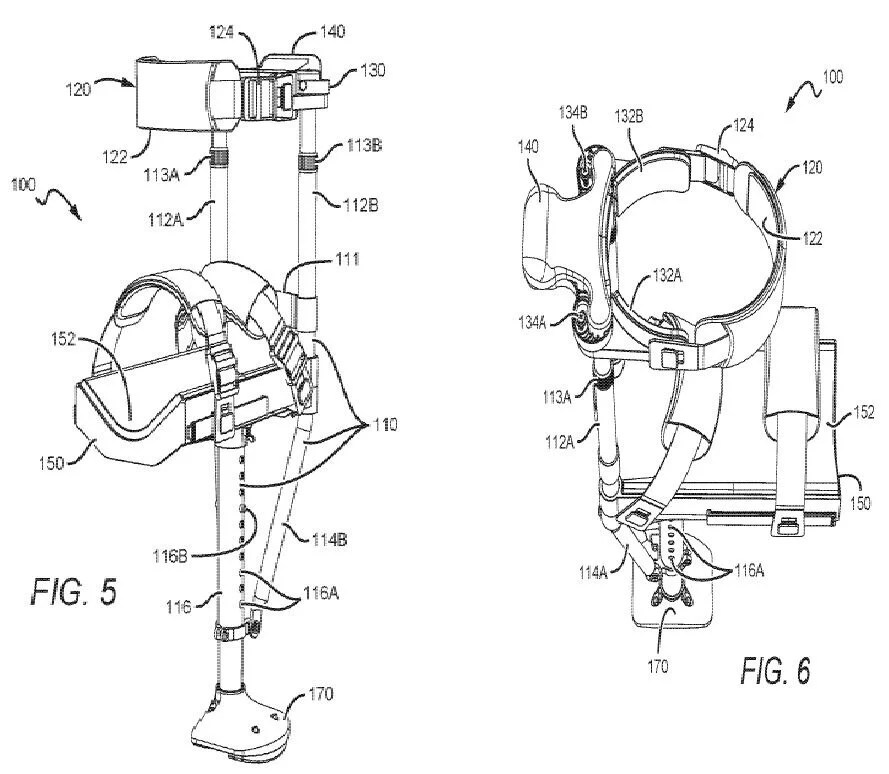

A recent PTAB decision illustrates this issue. The case is Appeal 2019-002282 (Application 15/203,409) and relates to a hands-free crutch. Claim 1 on appeal is as follows (with the underlined text at issue):

A crutch configured to accommodate different

circumference legs, comprising:

a frame;

a lower leg platform coupled to the frame;

a thigh fastener coupled to the frame through left and right arms, the left and right arms disposed to engage a user’s upper thigh;

independently adjustable left and right mechanisms configured to adjustably fix the angular positions at which the left and right arms, respectively, extend from the frame along a horizontal plane such that the angular positions of each of the left and right arms can be fixed at a plurality of angles along the horizontal plane relative to the frame and such that the angular positions of each of the left and right arms relative to the frame along the horizontal plane can be fixed at different angles from each other; and

an upper thigh contact surface coupled to the frame, the upper thigh contact surface disposed on the frame such that a corresponding front surface of the user’s upper thigh contacting the upper thigh contact surface is prevented from extending substantially forward beyond the front of the frame.

The underlined text relates to elements 134A/B (see below figures from the application). The examiner relied, in part, on a reference that showed some brackets that allegedly provided the claimed independent adjustment, even though it looked like the brackets only allowed linear motion (no angle).

The examiner here argued that because the bracket allowed some adjustment, it therefore allowed angular adjustment or linear adjustment as desired since the specification did not teach otherwise. (Notice the switcheroo here – the lack of teaching becomes a teaching).

The PTAB disagreed:

… the Examiner’s finding that brackets 52 function as clamps that would allow for angular adjustment of leg braces 54 appears to be based on speculation. Patentability determinations “should be based on evidence rather than on mere speculation or conjecture.” Alza Corp. v. Mylan Laboratories, Inc., 464 F. 3d 1286, 1290 (Fed. Cir. 2006).

While an examiner is often not convinced of deficiencies like this during prosecution, it can be a strong argument on appeal. Here, upon reversal, the case was then allowed.

Leave a comment