Oregon is Sasquatch country, and if you are lucky you can find some great little taverns in remote areas with their own take on the legend. However, not all likenesses are of the same quality. Likewise, not all USPTO rejections are of the same quality, either. Today we review a recent PTAB decision reversing a rejection for one of the most basic reasons there can be – the cited prior art was dated after the priority date of the application (in this case by three years). And do not think that this issue just slipped by the quality specialists at the USPTO – this particular rejection was actually added in the Answer on appeal and designated as a new ground of rejection, and was specifically and explicitly blessed by the TC director. The case is Appeal 2024-001019, Application 17/647,127.

Everyone reading this blog knows that in patent law under the first-to-file regime, a foundational rule is that for a document to qualify as prior art, it must predate the invention. This rule ensures that patent claims are only assessed against publicly available knowledge existing before the invention’s filing date, providing a fair and clear standard for evaluating novelty and non-obviousness. But, as many patent practitioners also know, things can get complicated when an examiner uses post-dated documents—not as prior art, but as alleged “evidence” to support their conclusions.

In the normal, traditional, context, the examiner’s use of prior art is generally limited to information and references that were available before the invention’s effective filing date. However, there are instances where an examiner’s approach may blur the lines of this rule. Complications arise when an examiner cites a document that was published after the invention’s filing date, not as prior art, but as some sort of “evidence.” Common examples include dictionary definitions, encyclopedic sources, or Wikipedia pages, cited to establish a general technical fact or to demonstrate how certain terminology is understood within a field. An examiner might use a non-prior-art document to argue that a specific term had a generally understood meaning at the time of the invention. Or they might cite it to claim that certain knowledge—like a natural phenomenon or widely acknowledged technical principle—was common in the field. In these cases, the examiner’s goal is not to directly challenge the novelty of the claim but to support an interpretation of terms or basic technical facts, such as to support inherency.

Examiner sometimes push the limits on this approach. Consider a situation where the examiner tries to use non-prior-art evidence to justify a motivation to combine prior art references. While there must have been a reason at the time of the invention to combine elements in a way that would lead to the claimed invention, examiners can sometimes blur the lines by arguing that some missing feature would be understood because of some technical aspects supported by non-prior art evidence. However, if the examiner’s cited motivation relies on information from a document that post-dates the invention, it’s anachronistic; a motivation to combine must be grounded in the knowledge actually available when the invention was made.

Turning to the cited case, claim 1 on appeal is reproduced below:

1. Dental implant configured to be inserted into a hole in jaw bone and to be at least partially situated in bone tissue when implanted, comprising:

a coronal implant region having a surface, wherein the surface is at least partly covered by an oxide layer with an average thickness in the range from 60 nm to 170 nm such that the coronal implant region exhibits a yellow color when viewed by the human eye, and the surface has an average arithmetical mean height surface roughness Sa in the range from 0.1 μm to 1.0 μm

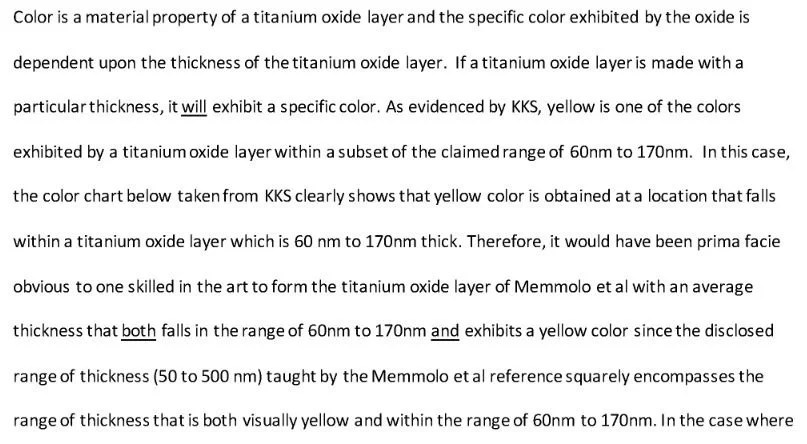

The examiner changed the rejection in the Answer due to the lack of prior art showing the oxide layer with an average thickness in the range of 60 nm to 170 nm. This specific claimed thickness range allegedly resulted in an interference color of the coronal implant region that is yellow or pink when viewed by the human eye. The cited art showed a much larger range (50-500nm). To remedy this problem, in the Answer, the examiner turned to new additional evidence, KKS (from three years after the invention), that allegedly linked the specific thickness range of an oxide layer to the yellow color.

The examiner explained as follows:

Note that because this was a new ground of rejection presented in the Answer, not only did the examiner have to get the other two signatories to agree, but also the TC director’s approval was required. Somehow all three other members (a supervisor, RQAS, and the TC director) all had no problem with citing non-prior art as supporting the reason to make the modification, as expressly cited above.

The PTAB reversed as follows (internal citations omitted):

The Examiner concludes that it would have been obvious to form the titanium oxide layer of Memmolo (i) with the narrower claimed thickness and (ii) so that it exhibits a yellow color by pointing to the KKS reference/website. As Appellant points out, however, “[t]he KKS website shows a 2022 date with no other indicated date,” which is after the earliest priority of the present application of 2018. Accordingly, the KKS reference is not available as prior art and thus the rejection is improper. Because the Examiner’s only evidence of the claimed narrower range and the color produced thereby is not a proper prior art reference, we do not sustain the Examiner’s rejection

So keep a sharp eye and a healthy dose of skepticism when you see an examiner citing non-prior art to support a prior art rejection. Whether or not you believe in Sasquatch, sometimes that shadowy figure in the examiner’s rejection might just turn out to be a myth.

Leave a comment