In patent prosecution, the inclusion of color in utility patent claims is a nuanced area that raises specific challenges, especially with respect to the printed matter doctrine. Although color may sometimes be relevant to the function of an invention, its use in claims can often lead to disputes about whether it serves a true technical purpose or is merely decorative or informative in nature.

The printed matter doctrine is a judicial principle used to assess whether certain claim limitations provide a patentable technical contribution. See previous posts here and here for example. According to this doctrine, purely informational content that doesn’t interact functionally with the claimed invention’s structure or operation can be deemed non-functional “printed matter.” In this context, “printed matter” doesn’t necessarily refer to actual print—it can apply to any information-bearing characteristic. For color, if it is deemed merely to convey information or distinguish parts of an invention without affecting operation or structure, it risks being classified as printed matter and disregarded as a non-limiting feature in the claim.

In many instances, examiners and the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) have found color to be non-functional printed matter. For example, in a recent case Appeal 2023-002208, Application 16/267,802, Milwaukee Tool sought to patent a set of nosepieces for riveting tools. Claim 1 is provided below:

1. A set of nosepieces, each nosepiece in the set configured to attach to a rivet setting tool, the set of nosepieces comprising:

a first nosepiece with a first longitudinal bore having a first diameter, a first detent, and a first O-ring configured to bias the first detent, the first O-ring having a first color; and

a second nosepiece with a second longitudinal bore having a second diameter that is different than the first diameter, a second detent, and a second O-ring configured to bias the second detent, the second O-ring having a second color that is different than the first color.

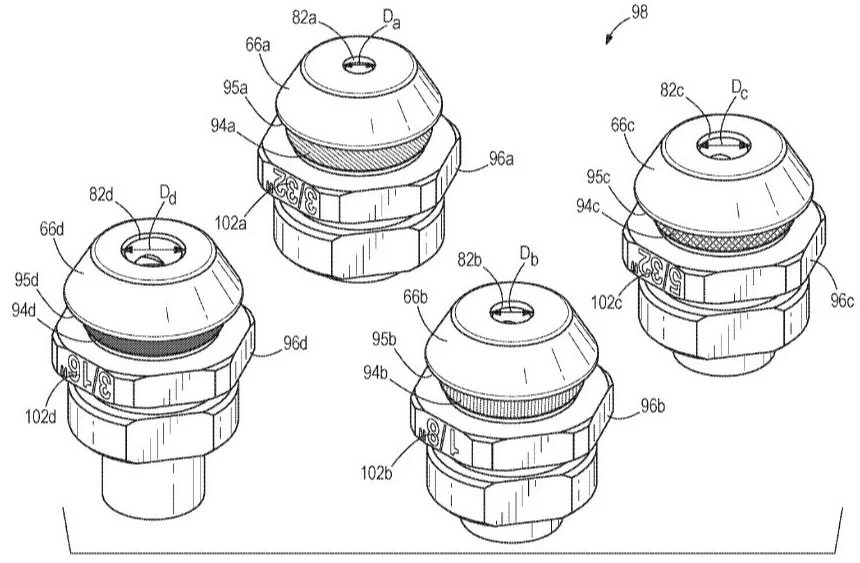

The figures below show the nosepieces as illustrated in the patent application, and as sold on the applicant’s website.

The PTAB upheld an examiner’s rejection without relying on the printed matter doctrine (as the board relied on disclosure of color in the cited art), but made clear that in future prosecution, the claimed color should be considered printed matter:PTAB in a footnote:

We also note, in the event Appellant elects to continue its patent prosecution efforts, that the O-ring colors recited in claim 1 appear to be nonfunctional descriptive material, which cannot be the basis to distinguish the invention from the prior art. See, e.g., In re Ngai, 367 F.3d 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2004); In re Gulack, 703 F.2d 1381 (Fed. Cir. 1983); Ex parte Bruce, Appeal No. 2020-003118, 2020 WL 8186186, at *12 (PTAB Nov. 27, 2020) (sustaining an examiner’s determination that “colors are printed matter and nonfunctional descriptive material having no new and nonobvious relationship to the slice thickness gauge” because “the recited colors are mere labels for the thicknesses shown on a thickness gauge, and . . . there is no functional relationship between the two”); Ex Parte Turner, Appeal No. 2012-002586, 2013 WL 1385354, at *2–3 (PTAB Mar. 29, 2013) (sustaining an examiner’s determination that the claimed color patterns on articles of apparel were “printed matter” that could not distinguish the prior art, because they connote “instructional information relating to sport teams’ identities and [are] not functionally related to how the garments are used”

To reduce the chances of claimed features, including color, being found non-limiting as printed matter, it can be useful to have support in the specification of a functional role for color. Here are some possible strategies depending on the context of the invention:

-

Describe a Functional Link Between Color and a Technical Result: Where color plays an active role in the operation of the invention, explicitly describe in the specification how it contributes to a technical outcome. For instance, if a particular color affects heat absorption, visibility under specific conditions, or interaction with other components, detailing this function may be helpful.

-

Provide Experimental Data or Examples: Experimental data showing how different colors lead to different technical effects (e.g., efficiency, response times, durability) can help reinforce the color’s functional nature. Consider examples that illustrate how the invention performs with and without the color, making it clear that color contributes directly to the invention’s performance.

-

Draft Claims to Emphasize Functional Interactions: In at least some claims, it may be helpful to describe how the color interacts with other structural features in a way that affects the overall function of the invention. Language that could suggest color is merely decorative or informational may be used by an examiner to support ignoring the features as printed matter.

-

Consider Alternative Wording: Rather than specifying a color outright, it may sometimes be beneficial to describe color properties (e.g., “light-absorbing surface”) that indirectly specify a color while emphasizing functionality.

By providing strong support for a functional link between color and the invention’s performance, the risk of color being disregarded as non-functional printed matter can be reduced and thus clearly connect color to the technical result.

Leave a comment